Visits from friends and relatives are considered crucial in the recovery and welfare of patients and research carried out on the severe restrictions imposed during the Covid pandemic indicates a clear detrimental effect on patients who missed visits from loved ones and friends. The impact on visitors has also resulted in an increased incidence of depression and anxiety being recorded. “I want to come home to live in the annexe through the court of protection. I miss my mum greatly and want to go home to her.” – note dated Friday 10th November.

Excluding or restricting visits should therefore be imposed only in exceptional circumstances where there are reasonable ground for believing that a visitor may have a detrimental effect on the patients therapy.

They are doing this as a punishment towards me but they are inflicting this punishment on my vulnerable daughter who does not want me banned and wants to come home at Xmas to see her cat. Likewise Lincolnshire Partnership Trust has destroyed my life and is destroying my health by their actions. It is unbelievable this is NHS “care”. There is no compassion, no feeling – they treat both carers and patients like dirt. That is my opinion anyway. There is clearly a culture of bullying here and my daughter’s life is at risk due to the fits she is suffering and low blood oxygen levels because of frequent injections and not forgetting missing of meals.

A decision to exclude visitors on the grounds of his or her behaviour or propensities must be fully documented and explained to the patient and where possible the appropriate person concerned. In the case of psychiatric patients the nearest relative should be informed of any visitor exclusions and supervision decision and if it is they who are excluded or supervised an explanation in writing is to be provided to them. The Nearest Relative has NOT been informed and nothing has been done properly. When I asked for an Impact Assessment they had not got a clue or else pretended they did not know. A nurse called Emily is going to speak to Elizabeth on Monday but I have notified her Advocate from Voiceability as I feel the advocate and solicitor she has been trying to contact time and time again should know about this.

A visitor may be excluded or restricted to visits under supervision if the visit is considered to be anti-therapeutic (in the short or long term) to an extent that a discernible arrest of progress or even deterioration of the patient’s mental state is evident or can reasonably be anticipated if contact is not restricted. This is being used as an excuse. There is no therapy and never has been. The fact is they want to sever contact with me and they are doing so without thinking about the rest of the family who cannot get through on her phone. Fact is I have discovered there has been a bad accident at Ash Villa and Elizabeth has shared information with me. The other fact is she misses home and wants to come home and has told everyone to this effect. Today she phoned me in the presence of a HCA. She complained of being starving hungry and missing meals has been going on for some time.

An impact assessment should be carried out in consultation with the patient to assess the impact of any denial or restriction of visits on the patient’s welfare. Where a patient lacks capacity or is impaired as to their capacity an assessment by a suitably qualified best interests assessor should be carried out to assess any negative impact that denial or restriction of visits may have on the patient.

No impact assessment has ever been carried out. I have asked them to put everything in writing.In addition to acting ultra vires with decision to rescind all S17 ground leave (punishment towards me) but inflicting upon Elizabeth’s health and welfare, today it became evident her phone has been taken away again by Castle Ward, Peter Hodgkinson Unit, LINCOLN COUNTY HOSPITAL RUN BY LPFT (LINCOLNSHIRE PARTNERSHIP TRUST, CEO namely Sarah Connery. The Trust is therefore vicariously liable for breaches of human rights law on the part of certain individual employees.

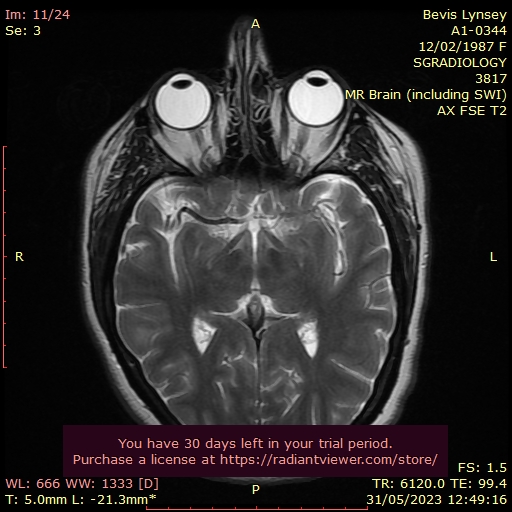

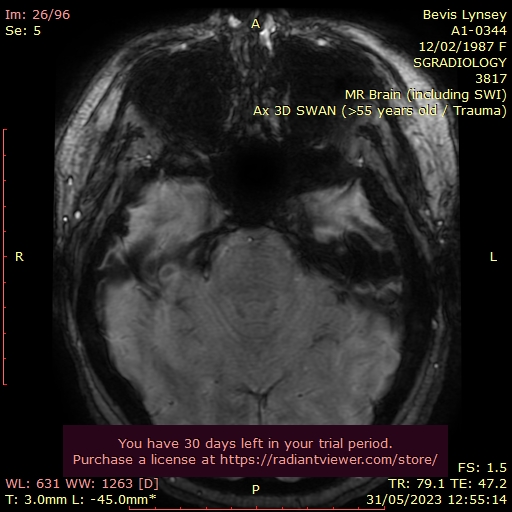

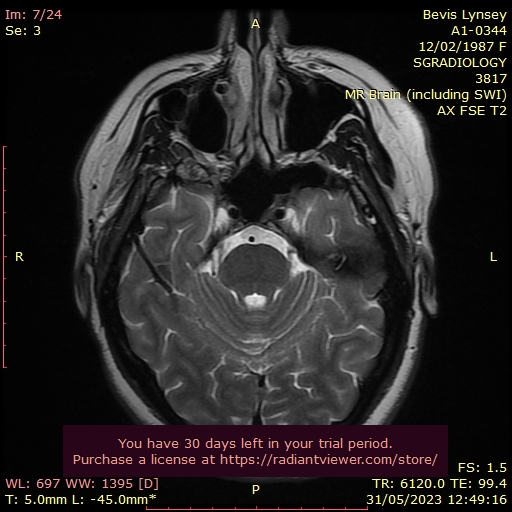

Today’s phone call from Elizabeth was in the presence of HCA Emma (a very nice young lady) in fact most of the HCAs are very nice and so are the OT’s so I told Elizabeth try not to get upset with those directly helping her. Via another HCA called Harry I overheard all S17 Ground leave was rescinded by Lucie Ann Waby, senior nurse. I can only assume recent restrictions are imposed by RC (Responsible Clinician) Dr Waqqas Khokhar who imposed the original on the grounds I am “a bad influence” “you are impacting on therapy” all said to be in line with Trust Policy and Guidelines. What therapy exactly might that be? There is no psychological input – said to be unnecessary in her case for the past 2 years. On virtually a daily basis Elizabeth is injected with RT when not even displaying behaviour of a nature that would warrant this. She clearly has something physically wrong to have what looks like a fit lasting from 2.00 pm until 7.30 pm and has a cyst on her head they do not want to do anything about. She has sent me several photos of plasters recently and has told us all that the injections really hurt her and they are given by male staff on occasions and often for no reason.

When having these “fits” never experienced before her blood oxygen levels are of great concern and very low and this is life threatening. Her body felt cold and clammy.

The Human Rights Act protects those whose rights are being abused and in this case that would include myself and my daughter Elizabeth. The following would apply in our case:

Art 8 HRA – right to privacy and right to family life

Art 2 HRA – right to life

Art 5 and section 6 HRA

Today, Sunday 26.11.2023 I received a call from Elizabeth, having previously not been able to get through to her when we pay a monthly phone contract via Vodafone. This is because her phone has been taken away yet again by LINCOLNSHIRE PARTNERSHIP TRUST CASTLE WARD LIKE IT HAD BEEN AT ASH VILLA. Elizabeth is being treated like a prisoner whilst being sectioned under S3 MHA just like she is on a DoLs. They are acting ultra vires.

A senior nurse called Lucie Ann Waby has already imposed enormous restrictions. I heard this confirmed in the background of a call when Elizabeth phoned me a few days ago. HCA Harry said she could not go to the shops in the hospital grounds and the name Lucie was mentioned. I then phoned Castle Ward and this was confirmed. It was further confirmed by text message from Elizabeth that Senior nurse Lucie Ann Waby was rescinding her tiny bit of leave given. I told Elizabeth “do not react against – I would be doing something about this.” “it is not you but me they are punishing” but what is bad is they are using my vulnerable daughter as a tool to punish me. On behalf of so many others who are being abused on the basis of human rights under shocking NHS care I will do everything I possibly can in this matter as it is one that is affecting me also and inflicting upon my health and wellbeing physically. I asked Elizabeth what she had been doing on the ward lately. She is said not to engage in things but from certain papers she has shared that is completely untrue. She likes cooking and has always wanted to be a chef since age 9. She likes art and crafts. She likes the OT’s on the ward and gets on OK with HCAs. We are talking about senior members of staff here who are behind these rules and acting ultra vires. Elizabeth said a nurse call Emily is coming to see her on Monday – dont know what Emily will be talking about but I pointed out to Elizabeth that everything needed to be put in writing. They are clearly not looking into her health and wellbeing and what impact such heavy restrictions are having.

Mobile Phones and Deprivations of Liberty

January 31, 2023

Is depriving a person of their mobile phone depriving them of their liberty? That was the very 21st century question confronting a High Court judge recently. Whilst his analysis concerned the position of a 16 year old, his conclusions apply equally to adults, writes Alex Ruck Keene KC (Hon).

It was common ground between the local authority and the Guardian that the significant restrictions to be placed upon the ability of the 16 year old in question, P, to use a mobile phone and other devices gave rise to a state imposed confinement to which she did not consent, and hence a deprivation of her liberty, which the High Court could authorise by exercise of its inherent jurisdiction.

MacDonald J, however, whilst acknowledging that this had been the practice to date (including by himself), decided in Manchester City Council v CP & Ors [2023] EWHC 133 (Fam) that it was necessary to consider the question in more detail, and reached the opposite conclusion.

Importantly, and identifying a point which is sometimes missed, MacDonald J made clear at paragraph 26 that the caselaw confirmed that “in this context, and historically, the concept of liberty under Art 5(1) of the ECHR contemplates individual liberty in its classic sense, that is to say the physical liberty of the person,” and that the reference to “security” in Article 5 “serves simply to emphasise that the requirement that a person’s liberty may not be deprived in an arbitrary fashion.” He noted that rule 11(b) of the UN Rules for the Protection of Juveniles Deprived of their Liberty also emphasised the concept of physical liberty,[1] defining deprivation of liberty as “any form of detention or imprisonment or the placement of a person in another public or private setting from which this person is not permitted to leave at will, by order of any judicial, administrative or other public authority.”

MacDonald J further identified at paragraph 37 that restrictions upon on access to, or the use of, telephones were most commonly considered by the ECtHR in the context of the Article 8 ECHR right to respect for private and family life, rather than under Art 5(1).

Applying these principles, MacDonald J recognised that:

45. […] for P, in common with many other young people of her age, her mobile phone and other devices constitute a powerful analogue for freedom, particularly in circumstances where she is at present confined physically to her placement. Within this context, I accept that the possession and use of her mobile phone, tablet and laptop, and her concomitant access to social media, is likely to equate in P’s mind to “liberty” broadly defined as the state or condition of being free.

However, MacDonald J continued:

However, this court is concerned with the meaning of liberty under Art 5(1) of the ECHR. Whilst I recognise that the Convention is a living instrument, which must be interpreted in the light of present-day conditions (see Tyrer v United Kingdom (1978) 2 EHRR 1 at [31]), over an extended period of time the Commission and the ECtHR have repeatedly made clear that Art 5(1) is concerned with individual liberty in its classic sense of the physical liberty of the person, with its aim being to ensure that no one is dispossessed of their physical liberty in an arbitrary fashion. The Supreme Court proceeded on that formulation of the proper scope of Art 5(1) in Cheshire West.

That meant, in turn, that:

46. […] in my judgment the removal of, or the placing of restrictions on the use of, P’s mobile phone, tablet and laptop and her use of social media do not by themselves amount to a restriction of her liberty for the purposes of Art 5(1). On the evidence currently before the court those restrictions do not act to deprive P of her physical liberty, but rather act to restrict her communication, so as to ensure her physical and emotional safety. The evidence set out earlier in this judgment demonstrates that the effect of those restrictions is to limit P’s communications with peers who might encourage her to engage in bad behaviour, with strangers who may present a risk to her and with family and friends when she is in a heightened emotional state. Within this context, the restrictions on the use of P’s devices for which the local authority seek authorisation do not, in my judgment, by themselves constitute an objective component of confinement of P in a particular restricted place for a not negligible length of time. In the circumstances, whilst they are steps at times taken without P’s consent and are imputable to the State, those restrictions do not, by themselves, meet the first Storck criterion [i.e. that P is subject to continuous supervision and control and prevented from leaving a restricted place for a non-negligible period of time].

The local authority argued that the restrictions upon her devices formed an integral element of the confinement to which P was subject (in circumstances where she was under other, more obvious restrictions such as supervision and physical restraint to protect from harm). Whilst MacDonald J accepted that they might, at time, be said to form part of a regime of continuous supervision and control, he reiterated that they did not act to restrict her physical liberty. Rather, their effect was:

65. […] to prevent P broadcasting online indiscriminately, to prevent contact from those advising her how to frustrate steps the placement takes to stop her from harming herself and others and to prevent her sharing details online with those who may pose a risk to her and restricting contact with those against whom she has alleged abuse. There is no suggestion in the evidence currently before the court that those restrictions constitute a necessary element of the deprivation of P’s physical liberty or of the manner of implementation of that deprivation of liberty. For example, the evidence before the court does not suggest that the restrictions on the use of P’s mobile phone, tablet and laptop and use of social media are required to ensure the effectiveness of the current measures that do operate to prevent her from leaving the placement, or that without those restrictions the current measures that operate to prevent her from leaving the placement would be rendered ineffective. In these circumstances, in my judgment the restrictions in respect of P’s phone, tablet and laptop and on the use of social media do not, even when considered in the context of the other elements of the other restrictions for which authorisation is sought, constitute an objective component of confinement of P in a particular restricted place for a not negligible length of time. Accordingly, it would in my judgment be wrong to authorise them under the auspices of a DOLS order [2] simply because they form part of the total regime to which P is currently subject in her placement.

Some might be wondering by this stage why MacDonald J was quite so keen to make clear that the restrictions on P’s devices did not give rise to a deprivation of her liberty. The answer he gave at paragraph 50 was an important one:

The difference between deprivation of and restriction upon liberty is one of degree or intensity and not one of nature or substance. But there is nonetheless a difference and that difference can have consequences. As I have noted above, restrictions of the type being imposed on P with respect to the use of her mobile phone, tablet and laptop, and concomitant limitations on her access to social media, are most naturally characterised as an interference with her Art 8 right to respect for private and family life. When considering them as such, before a court could endorse that interference it would have to be satisfied that that interference was necessary and proportionate, pursuant to Art 8(2). If however, those steps were instead to be considered and endorsed by the court by reference to Art 5(1), the exercise under Art 8(2) would be bypassed in respect of steps that constitute an interference in an Art 8(1) right. It is important that the court be careful not to allow its jurisdiction to make orders authorising the deprivation of a child’s liberty by reference to Art 5(1) to spill over into authorising steps that do not constitute a deprivation of liberty for the purposes of Art 5(1), particularly where those steps might constitute breaches of different rights, which breaches fall to be evaluated under different criteria. It may well be that one of the reasons for ECtHR adopting the narrow interpretation of word ‘liberty’ under Art 5(1) in cases such as Engel v Netherlands, limiting it to the classic concept of physical liberty, was to reduce risk of the Art 5 exceptions resulting in a de facto interference with other rights, without proper reference to the content of those other rights.(emphasis added).

MacDonald J’s conclusion meant that it was necessary to find an alternative route to authorise the restrictions (assuming that such restrictions were justified). This alternative route, he found, lay in the operation of parental responsibility (in P’s case, by the local authority under its shared parental responsibility under s.33(3)(b) of the Children Act 1989, P being the subject of a final care order. MacDonald J found that, ordinarily, a local authority relying upon s.33(3)(b) Children Act 1989 to impose restrictions on the use of devices to protect a child from a risk of serious harm would not require the sanction of the court, he did accept at paragraph 60 that:

circumstances that contemplate the use of physical restraint or other force to remove a mobile phone or other device from a 16 year old adolescent, even in order to prevent significant harm, is a grave step that would require sanction by the court, rather than simply the exercise by the local authority of its power under s.33(3)(b) of the 1989 Act, not least because such actions would likely constitute an assault. I am further satisfied that, in an appropriate case and where an order under Part II of the Children Act 1989 would not be available where a child is subject to a final care order, it would be open to the court to grant the local authority permission to apply for an order under the inherent jurisdiction, separate to any order authorising deprivation of liberty, that declares lawful the steps required to effect by restraint or other reasonable force the removal from a child of his or her devices, provided it is demonstrated that their continued use is causing, or risks causing, significant harm and provided that the force or restraint used is the minimum degree of force or restraint required.

MacDonald J emphasised that the threshold for making such an order – separate from the order authorising deprivation of liberty – would be a high one, requiring “cogent evidence that the child is likely to suffer significant harm if an order under the inherent jurisdiction in that regard were not to be made” (paragraph 71).

Comment

MacDonald J’s decision is a very useful reminder of the limit of the concept of deprivation of liberty: in this context, liberty, importantly, is not another word for autonomy. As Lady Hale put it in Secretary of State for the Home Department v JJ [2007] UKHL 45 (at paragraph 57):

My Lords, what does it mean to be deprived of one’s liberty? Not, we are all agreed, to be deprived of the freedom to live one’s life as one pleases. It means to be deprived of one’s physical liberty […] And what does this mean? It must mean being forced or obliged to be at a particular place where one does not choose to be: […] But even that is not always enough, because merely being required to live at a particular address or to keep within a particular geographical area does not, without more, amount to a deprivation of liberty. There must be a greater degree of control over one’s physical liberty than that.

In passing, it might be thought to be of interest that Lady Hale was clear in 2007 that deprivation of liberty included an element of overbearing of the person’s will, but by 2014 considered in Cheshire West that a lack of MCA-capacity to consent to confinement was sufficient, even if the person appears to be content. If you want to follow that rabbit hole, you might find this paper of interest.

It is interesting, and reassuring, to note that MacDonald J reached the same conclusions as to the human rights allocation of restrictions upon devices as was reached some years ago in the Court of Protection context by Mostyn J in J Council v GU & Ors[2012] EWCOP 3531. That the judgment did not refer to this case is likely down to the fact that (for better, or, I venture to suggest, worse) parallel furrows seem to be being ploughed by those concerned with deprivation of liberty in the context of children and adults.[3]

Be that as it may, MacDonald J’s observations about the need to be clear about which rights are in play, and what considerations need then to be taken into account in identifying who can determine and on what basis whether or not the interference is lawful are trenchant. They are also equally relevant in DoLS land in relation to adults. They reinforce the fact that restrictions which are not specifically directed at restricting the physical liberty of the person are not restrictions which can be authorised under DoLS. Such restrictions, whether they be upon devices, or upon contact, either need to be justified by reference to the (thin) legal cover available here under s.5 MCA 2005 or – more likely – need to be put before the Court of Protection so that the court can determine whether (a) such restrictions are in the best interests of the person; and (b) whether they are necessary and proportionate so as to satisfy Article 8(2) ECHR.

Alex Ruck Keene KC (Hon) is a barrister at 39 Essex Chambers. This article first appeared on his Mental Capacity Law & Policy blog.

[1] In passing, he could equally have noted that the interpretation of deprivation of liberty for purposes of these Rules derived from the interpretation of the concept for purposes of Article 9 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. The Human Rights Committee’s General Comment 35 on Article 9 makes clear in paragraph 3 that “[l]iberty of person concerns freedom from confinement of the body, not a general freedom of action.”

[2] As a plaintive and probably forlorn plea, it would be really helpful if practitioners and the courts could stop referring to inherent jurisdiction orders as “DoLS orders” as it perpetuates confusion with ‘actual’ DoLS, i.e. administrative authorisation under the Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards in relation to adults in care homes/hospitals.

[3] An issue identified by Sir James Munby in 2018, discussing in a speech for Legal Action Group the case of D at the point between his decision in the Court of Appeal and the decision of the Supreme Court, noting that “these cases lie at the intersection of three different bodies of domestic law – mental health law, mental capacity law and family law – where judicial decision-making is spread over a variety of courts and tribunals which, by and large, are served by different sections of the legal professions too few of whom are familiar with all three bodies of law. The existence of these institutional and professional silos has bedevilled this area of the law at least since the earliest days of the Bournewood litigation. One day, someone will write a critical, analytical history of all this – and it will not, I fear, present an altogether reassuring picture.”

As for the Oliver McGowan Training I do not see how this Trust is even capable of learning anything with regard to how to treat a vulnerable person when there has been complete abuse of power and process. The impact on us has been tremendous since moving and all we have come up against is severe bullying yet they are rated good by cqc. It has been the worst experience of my life and the very worst treatment we have ever come up against and most shockingly this is NHS care and not private.

On 10th November 2023 Elizabeth wrote “My idea”

“I want to eventually come home to live with my Mum in the Annex through the Court of Protection.

I miss my Mum greatly and want to go home to her”

Elizabeth is now a virtual prisoner on the Castle Ward, Peter Hodgkinson Centre, LINCOLN COUNTY HOSPITAL, punishment on me but inflicted upon her. Total and utter cruelty. This is a disgrace to the NHS as a whole. This will have knock-on detrimental effect on Elizabeth’s health and wellbeing especially with regard to deprivation of fresh air and exercise. The excuse given by Dr Waqqas Khokhar Responsible Clinician who has ultimate responsible for S17 leave is that I am apparently a “bad influence” and that the MDT of other 30 people agree that I am having a negative effect on ‘therapy/treatment”. From what I hear from Elizabeth this consists of practically daily injections of RT which is affecting her blood oxygen levels (recorded on very recent paperwork) and can be life threatening. Private MRI scans done show concerns on several images certain doctors did not want her to see a Neurologist or have fresh scans done going back over 2 years detention. However the former area of Enfield were taking her physical health seriously and so all neurologist appointments were cancelled as unnecessary upon moving to Lincolnshire. There has been no IMPACT ASSESSMENT done. When a decision has been made to ban someone or restricting someone in any way in terms of visiting an IMPACT ASSESSMENT should be done and everything put in writing with the Nearest Relative being informed.

When is a healthcare professional’s act non-medical, and how might such non-medical acts be classified?

One approach, analogous to the substantive due process inquiry employed by courts weighing the constitutionality of legislative acts, would involve consideration of the following questions:

1) Is a legitimate medical goal being pursued?

2) Are the means being employed legitimately medical?

3) Are the goals and means appropriately related? Accordingly, a healthcare professional acts medically when employing legitimate and appropriate medical means in pursuit of a legitimate medical goal.

In contrast, when the goals pursued or means employed are not legitimately medical, or when the two are not appropriately related, the act is medically ultra vires (“beyond the powers”)–that is, an act beyond the professional’s power or authority–and consequently non-medical.

If an act designed to achieve an end such as restricting visits had a purpose of simply punishing the visitor, to the detriment of the patient then it would have no legitimate medical purpose.

Denying a patient activities that are beneficial to them in order to apply some form of sanction is a matter ultra vires. This was the failing of the ‘token economy’ system used in psychiatric hospitals where patients were coerced into behaving in a particular way for favours. Not only is this a flagrant breach of the principlist ethics of beneficence & autonomy & possible non-maleficence but it represents a violation in many cases of the patients human rights.

Section 17 leave and visits from friends and relatives are rights not favours.

Medicating patient with prn medication for the purpose of keeping them quiescent is arguably a non-medical intervention and is often used to give staff a quiet time rather than to benefit the patient. The usual reason given is that the patient was distressed. There are many ways a distressed person can he supported without prn injections. Giving drugs in the is way is both ultra vires and ultra fines.

Medically ultra vires acts may be further sub-classified depending upon which prong of the above trident is defective. Where the goal of the act, though achievable, is not legitimately medical, the act is medically ultra vires because of goal illegitimacy, or medically ultra fines (“beyond the ends”).

Where the means employed are not legitimately medical, the act is medically ultra vires because of means illegitimacy, or medically ultra modos (“beyond the means”). Where the means and goals are not appropriately related, the act is medically ultra vires because of means-goals disjunction, or medically ultra nexus (“beyond the connection”).

Medical futility (where the medical goal in question, albeit legitimate, cannot be achieved by the act under consideration) represents the paradigmatic example of the latter.

Elizabeth who is being denied the very basics of human rights under this dreadful Trust has made a specific request:

Can I be present in court Mum. I said in front of Emma “yes you can” and both her and Emma or any other member of staff who would be accompanying Elizabeth should be booked into the very best of hotels seeing as LINCOLNSHIRE PARTNERSHIP TRUST HAVE PUBLIC MONEY TO BURN.

THE HONOURABLE MR JUSTICE PETER JACKSON

Between:

THE LONDON BOROUGH OF HILLINGDON

Applicant

– and –

STEVEN NEARY (by his litigation friend, the Official Solicitor)

First Respondent

– and –

MARK NEARY

Second Respondent

– and –

THE EQUALITY AND HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION

“The DOL scheme is an important safeguard against arbitrary detention. Where stringent conditions are met it allows a managing authority to deprive a person of liberty at a particular place. It is not to be used by a local authority as a means of getting its own way on the question of whether it is in the person’s best interests to be in that place at all. Using the DOL regime in that way turns the whole spirit of the MCA on its head, with a code designed to protect the liberty of vulnerable people being used instead as an instrument of confinement. In this case far from being a safeguard the way in which the DOL process was used to mask the real deprivation of liberty which was the refusal to allow Stephen to go home”

Jackson J.

Manchester City Council v CP & Ors [2023] EWHC 133 (Fam)

Restrictions around a person’s access to their mobile phone or other device are not usually specifically directed at restricting P’s physical liberty. As such, they are not usually restrictions that can be authorised under a Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS) authorisation.

Removing or restricting an individual’s use of their mobile phone is an interference with that person’s human rights under Article 8 ECHR (right to respect for private and family life). Any interference with that right would therefore need to be necessary and proportionate – either to safeguard and promote the person’s welfare or to protect the health and safety of others and decided under a procedure prescribed by law. A range of factors may need to be considered such as;

whether the person consents to the restriction,whether they lack capacity to do so but such restrictions are in their best interests and there are no objections to the same,whether the person is detained under the Mental Health Act and if so, the interplay between their mobile/device access and their mental health or associated risks,where the person is under 18, who has parental responsibility and what their views are,the extent, likely duration and impact of the restrictions on the person’s life,where the restrictions are significant and likely to be ongoing for some time, where there is an objection or for example where related physical restraint is required, whether court approval is likely to be required.

The necessary and proportionate elements require evidence not just an opinion.

The Mental Health Act (MHA) Code of Practice provides some helpful guidance on this issue where the person is in receipt of in patient mental health care. Chapter 8 of the Code highlights the fact that patients should have every opportunity to maintain contact with family and friends by telephone, mobile, e-mail or social media. Hospital staff should make conscious efforts to respect the privacy and dignity of patients as far as possible, which includes communicating with people of their choosing in private. It goes on to state that when patients are admitted, staff should assess the risk and appropriateness of them having access to their mobile phone and other electronic devices and this should be detailed in the patient’s care plan. Patients should be able to use mobile phones and other electronic devices if deemed appropriate and safe for them to do so and access should only be limited or restricted in certain risk-assessed situations.

The MHA Code stipulates that mental health hospitals should have policies on the possession and use of mobile phones and other devices, and on the use of social media, which should not seek to impose blanket restrictions on patients.

Government to legally make visiting a part of care

Government announces proposed legislation on visiting in health and care settings

New regulations will make visiting a legal requirement for hospitals, care homes, mental health units and other health and care settings

Care regulator will have new powers to make sure providers are allowing families to visit loved ones

People in care homes and hospitals will be able to have visitors in all circumstances, thanks to the government’s plans to bring forward new legislation.

Health and care settings should be allowing visits, according to the guidance from the government and NHS England currently in place, but there are reported cases where visiting access is being unfairly denied.

As a result, the government is seeking views from patients, care home residents, their families, professionals and providers on the introduction of secondary legislation on visiting restrictions.

The new legislation will strengthen rules around visiting, providing the Care Quality Commission (CQC) with a clearer basis for identifying where hospitals and care homes are not meeting the required standard.

The government recognises the contribution that visiting makes to the wellbeing and care of patients attending hospitals, and residents of care homes, as well as the emotional wellbeing of their families and so is seeking views on what the new rules will look like.

For health settings, regulations will be reviewed in both inpatient and outpatient settings, emergency departments and diagnostic services in hospitals, to allow patients to be accompanied by someone to appointments.

Minister for Care, Helen Whately said:

I know how important visiting is for someone in hospital or living in a care home, and for their families. I know from my own experience too – I know what it feels like to be told you can’t see your mum in hospital. That’s why I’m so determined to make sure we change the law on visiting.

Many care homes and hospitals have made huge progress on visiting and recognising carers since the pandemic. But I don’t want anyone to have to worry about visiting any more, or to face unnecessary restrictions or even bans.

I have listened to campaigners who have been so courageous in telling their stories. I encourage everyone who cares about visiting to take this opportunity to have your say on our plans to legislate for visiting.

Minister of Health, Will Quince said:

Most hospitals and care homes facilitate visiting in line with guidance, but we still hear about settings that aren’t letting friends and families visit loved ones who are receiving treatment or care.

We want everyone to have peace of mind that they won’t face unfair restrictions like this, so we want to make it easier for the CQC to identify when disproportionate restrictions and bans are put in place and strengthen the rules around visiting.

It’s important that people feedback on the consultation, we want to make sure the legislation is right for everyone. If you’ve experienced unjust visiting bans, please share your experience.

Challenges around visiting were exacerbated during the COVID pandemic, with many health and care settings restricting and banning visits to stop the spread of the virus, ease pressure on the NHS and reduce the risk of transmission. Since restrictions were eased and there was a return to normality, many health and care settings have made efforts to return to pre-pandemic visiting. There are however still instances where, families and friends continue to face issues with visiting across the health and care sector.

The CQC does currently have powers to clamp down on unethical visiting restrictions, but the expected standard of visiting is not specifically outlined in regulations. Current guidance from government and the NHS is clear that all care homes and hospitals in England respectively are expected to facilitate visits in a risk-managed way, such as through the use of face coverings in the event of an outbreak or in the reduction of the number of visitors at one time.

Patricia Mecinska, Assistant Director of Patient Experience at King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust said:

At King’s, our teams recognise the invaluable contribution that friends, carers and loved ones make to the patients under our care, including supporting us to provide care that’s respectful of our patients’ needs, so enabling them to make a positive recovery. Plans to involve care supporters in a more formalised way will be welcomed by many patients and will aid us in delivering our vision of providing outstanding care to patients and communities.

The hospital visiting guidance also includes an expectation that patients can be accompanied to hospital appointments when needed.

With the new legislation, the CQC will be able to enforce the standards by issuing requirement or warning notices, imposing conditions, suspending a registration or cancelling a registration.

Elizabeth has a full report on PTSD and she has consistently been denied the correct treatment and therapy.

Holding Elizabeth a virtual prisoner is only going to impact on what has already been diagnosed in the past and been completely and utterly ignored by LINCOLNSHIRE PARTNERSHIP TRUST.

For any others like me going through hell I want to share with you things that you cannot just find out through all helplines and charities and I intend to share all my templates for pre action protocol together with the correct form to use if your Trust/Council is acting ultra vires.

Please get in touch and I will be more than happy to help for anyone who is going through similar to us.